This article was written for the Stonecoast MFA blog & newsletter by Meghan Vigeant in 2020. (archived)

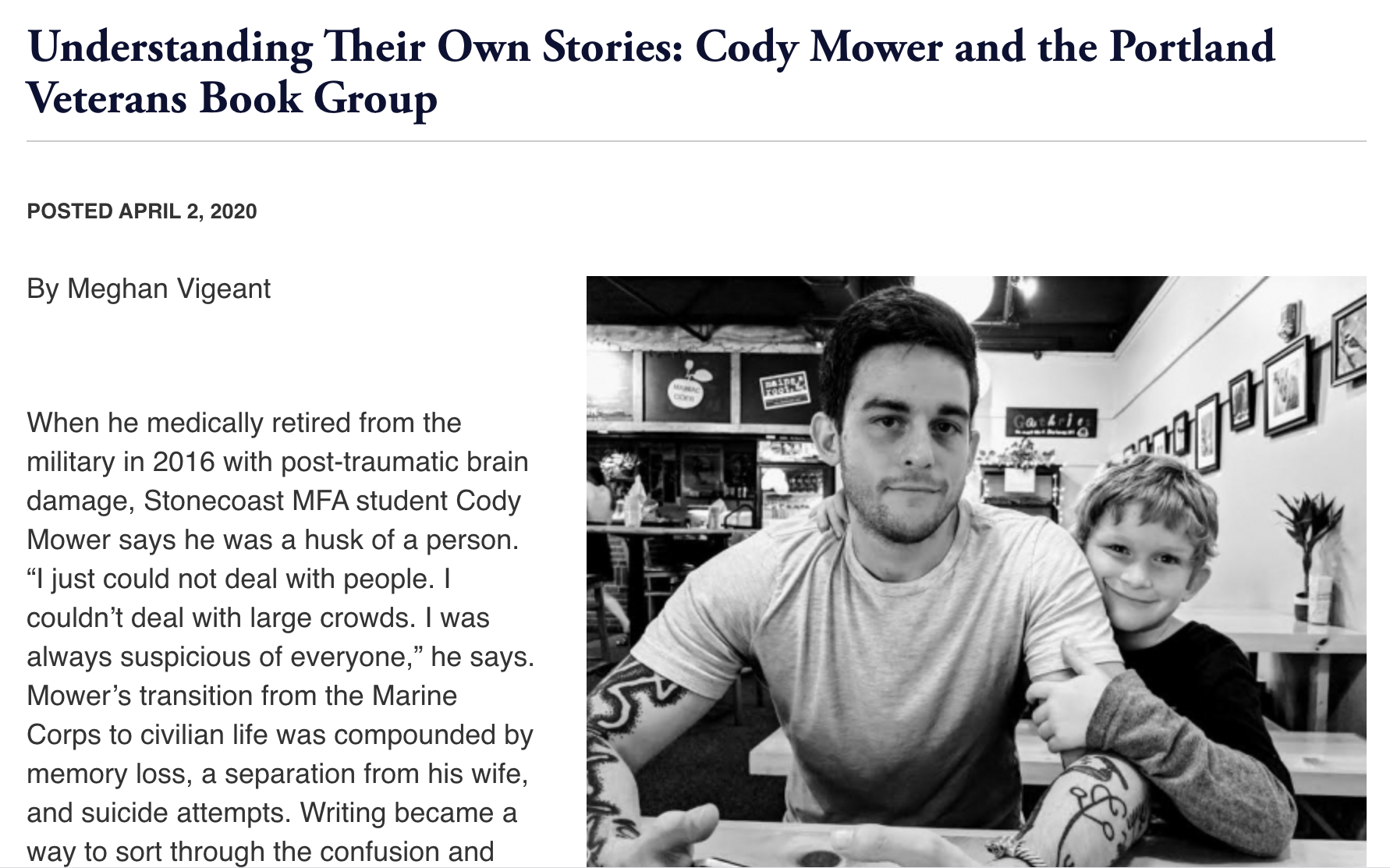

When he medically retired from the military in 2016 with post-traumatic brain damage, Stonecoast MFA student Cody Mower says he was a husk of a person. “I just could not deal with people. I couldn’t deal with large crowds. I was always suspicious of everyone,” he says. Mower’s transition from the Marine Corps to civilian life was compounded by memory loss, a separation from his wife, and suicide attempts. Writing became a way to sort through the confusion and anxiety. “I lost a few years that I just can’t get back—memories that are just not formed,” says Mower. “Part of my writing is about mourning that loss.”

For his first semester at Stonecoast, Mower was paired with faculty mentor Faith Adiele. “She really helped me explore male warrior culture, which is a mind-bending topic,” he says. Now, Mower writes about recovery stories in memoir and fiction. He is currently at work on a fiction piece that explores flashbacks and panic attacks as a supernatural force. “I want veterans that are in a similar spot to read my writing and realize that you can rebuild your life,” Mower says.

Once a month, Mower leads the Portland Veterans Book Group for the Maine Humanities Council. They read books like The Odyssey by Homer, In Pharaoh’s Army by Tobias Wolff, Tribe by Sebastian Junger, and Roughhouse Friday, a memoir by Stonecoast alum and local writer, Jaed Coffin. They talk about the challenges and heroic deeds in the books, but they also talk about the trauma of war and how our culture pushes toxic masculinity on young boys. While the focus is not on personal experiences, the discussions give veterans a safe space to bring it up. “My goal is to give veterans access to language to help them better understand their own stories,” Mower says.

In addition to the Portland group, Mower also leads Odin’s Warrior Tribe, an online book group for veterans, and he mentors veteran writers one-on-one.

As a trauma-informed facilitator, Mower is aware of triggers. He lets his writers know it’s okay if they can’t remember things. “I like to introduce the science of trauma, how the brain doesn’t store memories the same way,” he says. This is a concept he was introduced to during a Stonecoast graduate student presentation. The book groups often discuss characters’ traumas, and that might allow veterans to discuss their own experiences too—but Mower doesn’t push it. Sometimes people cry or get emotional. He’s there to remind them: “These are heavy subjects. It’s okay. No one’s here to judge.”

Mower is trying to debunk the idea that all vets are supposed to be tough guys. “I think toxic masculinity is a denial of the self at the expense of others,” he says. “They’re hiding their pain and don’t know how to express it.” He points to the book How To Think Like a Roman Emperor by Donald Robertson, a behavior cognitive therapist who explores Stoicism. Robertson writes, “‘Having a stiff upper lip’ is not what Stoics had in mind. A man is not made of iron and stone, but flesh and blood.” Mower sums up the book’s ideas: “Getting help when you need it, kindness, justice, fairness are all parts of Stoicism which have somehow been left out in modern times.”

“Most veterans stop short of being expressive with words because there’s a stigma that writing is somehow flowery or belongs in a feminine sphere,” Mower says. He insists to his reading groups that there’s nothing emasculating about learning to use their words. By reading books like Tribe and Roughhouse Friday and discussing them, the veterans in his book group have begun to change their language. “Changing external dialogue helps change internal dialogue and how you come to grips with yourself. That’s a good way of building better human beings in general,” Mower says. “But for guys that are dealing with stuff, I think there’s no medicine quite like it.”

As a writer and a teacher, Mower feels indebted to his mentors and the Stonecoast community, “[They’ve] helped me feel at ease with writing my trauma, and doing it unabashedly,” he says. Through the Stonecoast community, Mower has been exposed to more books, ideas, and new ways of thinking he can share with his writers and reading groups. He’s grateful to pay it forward. “The writing community depends on this cycle of giving and sharing knowledge and kindness,” Mower says. “Once you become a part of it, it's like taking a sacred unspoken vow to give as good as you get.”

Meghan Vigeant is Stonecoast MFA candidate in creative non-fiction. This semester she is assisting Stonecoast’s WISE program (Writing for Inclusivity and Social Equity) and preparing her thesis for graduation.